When most people hear the word archaeology, they immediately picture Indiana Jones escaping booby traps and sprinting out of collapsing temples with ancient relics in hand.

Yeah, it’s cool and all, sure — but let’s be honest, that’s not how archaeology actually works.

The reality behind it is far more grounding (no pun intended). It involves careful excavation, data analysis, and cultural research rather than fighting Nazis or uncovering mystical relics.

There are lost civilisations to find, ancient scripts to reconstruct, and thousands of years of human history waiting to be interpreted through artefacts.

How does one become an archaeologist, though? Well, by getting an archaeology degree, of course.

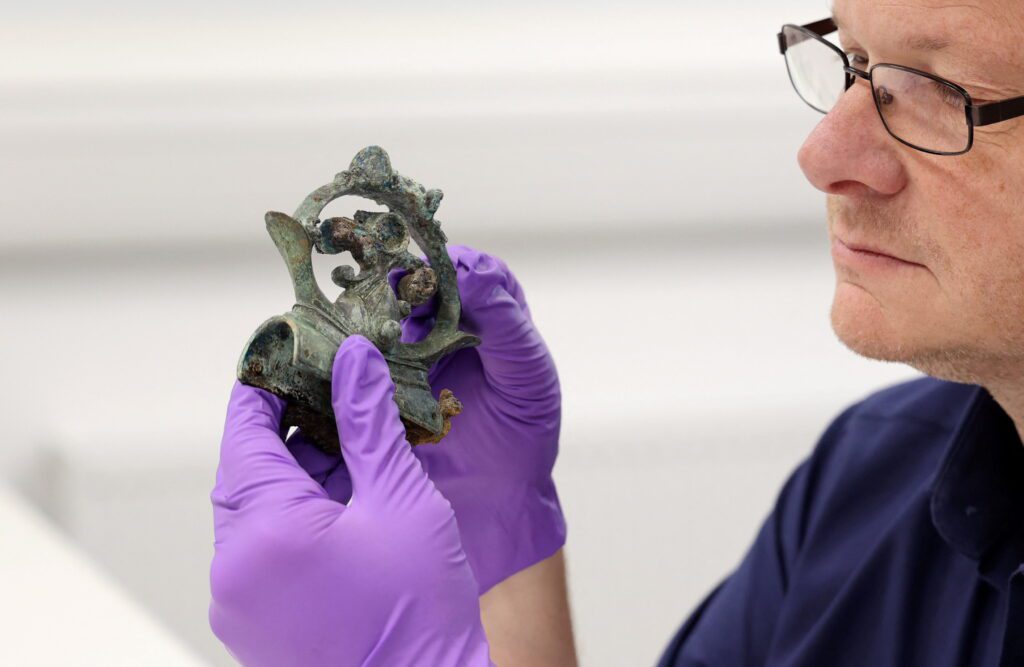

The oldest tools ever found were handmade stone anvils, cores, and flakes, dating back to 3.3 million years ago. Source: AFP

Getting a degree in archaeology doesn’t teach you how to swing from vines or outrun boulders — it teaches you how to ask the right questions about the past and how to find evidence to answer them.

You’ll learn how to use tools like GIS mapping, carbon dating, and even DNA analysis to piece together how people lived, died, traded, migrated, and built the foundations of the world we live in today. It’s less about adventure-chasing and more about puzzle-solving.

And here’s the thing: the study of archaeology isn’t just about the past — it’s about understanding people — how they adapt, innovate, and leave traces behind.

That’s what makes an archaeology degree so great. However, people still have reservations about whether they should pursue this degree path. Will it make money? What can they do with it? Can you even get jobs?

Well, we’re here to answer all these questions for you.

Fun fact: Italy boasts the most UNESCO World Heritage archaeological sites, with a whopping 58. China comes in second place with 56, followed by Germany with 51. Source: AFP

Here’s what you can do with an archaeology degree:

You can most definitely get jobs

So, you’ve got an archaeology degree — or you’re thinking about getting one — and now you’re wondering, what’s next?

While you might picture Indiana Jones-style adventures, there’s actually a whole world of career paths that go way beyond tomb raiding. Whether you love digging in dirt, teaching others, or preserving priceless artefacts, this degree can take you in many different directions.

Archaeologists or field technicians

Average annual salary: US$69,166

If you’re the type who dreams of discovering lost cities or digging up ancient secrets, becoming an archaeologist or field technician might be right up your alley.

These are the folks in the industry who get their hands dirty (literally) surveying sites, excavating ruins, and analysing artefacts to piece together stories from the past.

As an archaeologist, you’ll be able to work with universities, cultural organisations, museums, or government agencies to help protect and understand human history.

Meanwhile, as a field technician, you’ll become the trusty sidekick, often on the front lines of excavation, helping with mapping and ensuring every bone, shard, or coin is recorded with care.

Dr. Marina Escolano-Poveda is a Senior Lecturer in Classics/Ancient History and Egyptology at the University of Liverpool. Source: Dr. Marina Escolano-Poveda

Educator (professor or history teacher)

Average annual salary: US$58,099 to US$114,792

For those who aren’t fans of the outdoors but are still deeply passionate about the study of archaeology, this is the ideal job for you.

With additional qualifications, archaeology graduates can become professors at universities or history teachers in schools, passing on their passion for the past to the next generation.

That’s something Dr. Marina Escolano-Poveda, a Senior Lecturer in Classics/Ancient History and Egyptology at the University of Liverpool, is doing.

“I chose to become a professor because I like to be able to combine doing research with transmitting the results of this research to the next generations,” she shares.

“Witnessing your students develop in their careers, from those early days as undergraduates when everyone is a bit lost, to completing their PhDs, is an unparalleled experience. Teaching is also the best way to continue learning. Class discussions can also have a profoundly positive impact on research, yielding great insights from the most unexpected questions.”

To become a professor, Marina first pursued a licentiate degree in History at the Universitat d’Alacant, followed by a second licentiate degree in Ancient History from the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

Later, she completed a seven-year PhD in Egyptology at Johns Hopkins University.

Researcher

Average annual salary: US$60,710

Seeking a quieter, scholarly environment? Becoming a researcher may be your thing.

You’ll delve deeply into specific periods or topics, contributing to academic publications, documentaries, or museum exhibits.

Curator or museum education officer

Average annual salary: US$75,929 to US$76,262

If you enjoy being surrounded by artefacts, becoming a curator or a museum education officer may be perfect for you.

As a curator, you’d be responsible for acquiring, preserving, and displaying historical objects, often creating exhibitions to showcase the story of the past.

A museum education officer is the bridge between the collection and the public. You’ll develop interaction programmes, workshops, and tours to bring the history to life.

Heritage consultant

Average annual salary: US$103,425

Heritage consultants advise on how construction or development projects may impact historical sites, collaborating with planners to strike a balance between progress and preservation — often getting involved at the early stages of the projects.

Your tasks also include research, undertaking site visits, writing heritage impact assessments, and preparing conservation plans.

Project manager

Average annual salary: US$60,710

As a project manager, you’ll be tasked with keeping archaeology digs, research initiatives, or museum projects running smoothly.

Handling budgets, schedules, and teams is also a part of your job scope. In other words, you’re the behind-the-scenes heroes who make sure discoveries see the light of day.

Kim Jinoh is a PhD in Archaeology candidate at Peterhouse, University of Cambridge. Source: Kim Jinoh

You can help the world understand life better

Archaeology is a time machine for the curious. It uncovers forgotten artefacts and structures, as well as reconstructs long-lost societies, revealing what daily life looked like centuries ago.

Ancient tools, pottery, and architecture allow researchers to map out food habits, trade networks, and social interactions — for example, the excavation of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa in modern-day Pakistan.

The excavation provided insights into he beliefs and rituals of the Harappans, and the presence of large public baths at Mohenjo-Daro suggests the importance of ritual cleanliness and community gatherings, according to ExploreAnthro.com.

For Kim Jinoh, a PhD candidate in Archaeology at the University of Cambridge, it’s the study of historical texts that explains warfare and political events of the past.

“I’m trying to find the evidence of the inherent instability within Iron Age settlements,” he shares.

“It’s an essential study because people assume that things around the world are fixed and static, but that isn’t the case. Understanding how settlements within larger Iron Age settlements interact may help us comprehend how society functions and how we can make contemporary society more sustainable. Past societies are not that different from today’s.”

But knowing this means that you’ll have to move abroad to study and visit sites of the ancient civilisation.

Fun fact: Machu Picchu is earthquake-proof, and llamas are not actually native to the area. Source: AFP

You can travel the world

The best part about having an archaeology degree? You get to travel the world — just like Kim and Marina.

“I had the opportunity to visit Luxor in Egypt for an excavation trip,” Marina shares. “I got to see many temples and pharaoh tombs. Visiting those places can give us an idea of the religious and ceremonial side of Egypt, as well as the problem that many ancient Egyptians faced.”

However, Marina’s most memorable trip was to Alexandria, Egypt. It revealed to her the lesser-known aspects of ancient Egypt.

“If I were to stay in Spain, I wouldn’t be able to learn what I’m passionate about,” says Marina. “I had to leave my country to study Egyptology abroad, and because of that, I get to travel the world.”

For Kim, studying archaeology has taken him to different parts of the world, including secluded areas.

“My favourite site is an Iron Age settlement located at the border of Germany and Switzerland, particularly in the city of Blumberg and Rhine Falls,” he shares. “My team and I stayed with a local farmer and learnt about the local life. There was even a medieval bridge that I got to cross over into Switzerland.”

Kim even had the opportunity to travel to a secluded part of Russia for an excavation trip.

“I joined my supervisor on an excavation project in collaboration with Russian archaeologists,” says Kim. “It was in a very remote part of Tuva Republic, and it was the most remote part of the world I’ve ever been to.”

It was in the middle of nowhere that there was no electricity, and Kim had to store food in an underground cellar. Despite its seclusion, Kim learnt a lot that he was able to apply to his PhD.